Pipelines Part 2 - Pipes and Writers

NEEDS WORK - this text was migrated from a proposed blog article and needs restructuring to be suitable as a docs item, and updating to the current API

In part 1 we had a look at what problems attempt to solve and introduced the “memory pool”. So now let’s see what we can do with it by introducing the “pipe” and comparing it to the familiar Stream. Before we can do that we need to define some configuration options (PipeOptions) - the most important of which is : the MemoryPool:

// ensure this gets disposed later

var pool = new MemoryPool();

// we can reuse this between multiple pipes

var options = new PipeOptions(pool);

// create our pipe

var pipe = new Pipe(options);

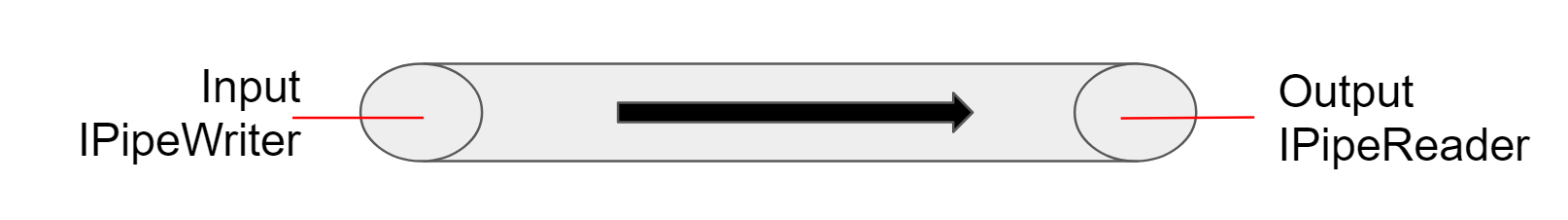

This is somewhat surprising when compared to Stream, because Stream is an abstract base-type, and you need to instantiate a specific type of stream. In pipelines, the Pipe is concrete and all the magic happens at the ends:

As you can see, a pipe has a very distinct direction, with separate APIs for pushing data into a pipe (IPipeWriter) and reading data from a pipe (IPipeReader); note that the pipe is itself the Input and the Output, so the following two options are identical:

async Task DoSomethingAsync(IPipeWriter reader) {...}

//...

await DoSomethingAsync(pipe.Output); // option 1

await DoSomethingAsync(pipe); // option 2

This is quite different from a Stream that has very ambiguous semantics for input and output - some stream implementations only support read or write; some stream implementations support read and write but talking to the same underlying data (FileStream, MemoryStream) - and some stream implementations support read and write, but where read and write refer to completely separate data (NetworkStream). This means that if you are dealing with a bidirectional data source, you simply need two pipes - one for the input, and one (facing the other way) for the output.

In pipelines, the role of the pipe is to negotiate with the things producing or consuming data, making use of the memory pool. Essentially, it handles all the buffer and semantics and deals with activating the two ends when needed.

Writing to a pipe

The first thing we probably want to try is writing data to a pipe. Now, a lazy but bad way of doing this might be the WriteAsync extension method that takes a byte[]:

// not great; don't do this

await pipe.WriteAsync(

Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes("Hello, world!\r\n"));

you might reasonably wonder why this is “bad”. Compare back to the list of objectives behind pipelines from part 1, and we’ve violated two of them:

- we’ve allocated a trainsient

byte[]that holds our data - we’ve forced it to copy the data from transient buffer to the actual buffer that we want to use (the one from the memory pool)

You’d think that writing an arbitrary string to an output was a simple enough thing, but it actually requires a surprising number of concepts. So: rather than dive in at the deep end, let’s go back a few levels and just write a few bytes (maybe 0x10, 0x20, 0x30 - why not?) to the pipe without a helper method:

First, we ask the writer for some space to write into; in this case, we only want 3 bytes, so we can ask for that:

WritableBuffer wb = writer.Alloc(3);

A WritableBuffer represents the state of an in-progress attempt to write, and essentially provides us with access to successive parts of blocks obtained from the memory pool (that we looked at in part 1). The WritableBuffer maintains a logical position of what we’ve written - which might cover multiple blocks.

Usually, we will be writing lots of things at the same time, so by specifying the number of bytes we want to write, the pipe can check whether there is enough space for the 3 bytes at the end of the current block on the pipe, and if so it can allow us to keep appending there; if there were only 2 bytes left (or no active block at all), it can consider the previous block as “done”, request a new block from the memory pool, and make the fresh block available to us.

An alternative approach is to just use writer.Alloc() without specifying an amount to ensure; in that case, it is the consumer’s job to check how much space is available in the WritableBuffer, and only write that much - then request a new one. This is especially important when handling larger quantities of data, an in particular when the amount of data that we want to write might be larger than the block size of the memory pool, since writer.Alloc(hugeSize) is likely to fail.

Once we have the WritableBuffer, we need to write to it. It provides a property that provides the unused space in the active block:

Memory<byte> memory = wb.Buffer;

Memory<T> is a very important type for us to understand. It is essentially an value-type (a readonly struct) that provides indirect access to an arbitrary contiguous block of memory. This is often a slice of an array (as it is with the default MemoryPool that pipelines provides), but it could also relate to memory accessed via a pointer, or some sub-range of a string. A key point here is that unlike an array (T[]) or string - it doesn’t necessarily start at the start of the array/string - it is more comparable to the ArraySegment<T> that has existed (largely unused) in .NET for a long time. Additionally, you can “slice” within a memory to look at smaller pieces:

// create a "memory" that refers to the 6 bytes

// offset 2 from the start of the current memory

// (essentially "skip 2, take 6")

Memory<byte> chunk = memory.Slice(2, 6);

As you might expect, it provides a .Length, but it doesn’t have an indexer - meaning: the following doesn’t work:

memory[0] = 0x10; // does not work

The reason that this doesn’t work is the word “indirect” in the previous paragraph; what we actually want to get hold of is the “span” (Span<T>), which is the heavily optimized actual access to a chunk of memory. But because of the “indirect”, we should consider fetching the span to be not free, so we only want to do that once:

Span<byte> span = memory.Span;

span[0] = 0x10;

span[1] = 0x20;

span[2] = 0x30;

Now; Span<T> is a very interesting type. As you can see, it behave a lot like an array - including having a .Length etc. This type is a very direct access to memory, and is highly optimized by the JIT. Because of the semantics of Span<T> (and the types of memory it can refer to, which includes stackalloc memory and other stack-only data), it is a ref struct, which means: it is only ever allowed to exist on the stack. This in turn means that we cannot have a Span<T> field on regular class or struct, but it also means that we can’t have a Span<T> local variable in an async method, since async continuations work by building a state machine that might need to end up in an object (on the heap).

This requirement to not have Span<byte> in an async method is very important in pipelines, since (from part 1 of this blog), async is a key goal of pipelines; we’ll look at how we avoid this being a problem shortly.

If all we want to write is those 3 bytes, we can finish writing:

wb.Advance(3);

wb.Commit();

The Advance(3) tells the buffer that we have actually written 3 bytes - if we access wb.Buffer again, we’ll find that the Memory<byte> we get back is now 3 shorter (and it now starts 3 bytes further into the block). In the cases when we might need to write multiple blocks, we can use Ensure(size) to make sure that we have a required amount of space for the next operation.

The Commit() tells the pipe that we’re finished with that WritableBuffer and to consider the written bytes available for consumption. Once Commit() has been called, it is not possible to add more data to it.

Marc suggests:

- the current API to get a span is awkward

- it is very messy having two “size” operations (

AllocandEnsure)

how about we make Alloc parameterless and just create the WritableBuffer, remove .Buffer, and delegate getting the span to Ensure, perhaps renaming it to GetSpan()?

example usage:

var bw = writer.Alloc();

var span = bw.GetSpan(3);

span[0] = 0x10;

span[1] = 0x20;

span[2] = 0x30;

writer.Advance(3);

//...

writer.Commit();

This feels so much cleaner.

I strongly suggest that this should be the case for IOutput too; the Enlarge and GetSpan() should proably be merged in the same way.

(end of Marc suggests)

Note that calling Commit() does not guarantee that the data actually goes to the reader; the Pipe will assume that we’re probably about to add more to the last block. To ensure that it is made availab, we use FlushAsync(). This method is available on the WritableBuffer:

await wb.FlushAsync();

Note that the FlushAsync() call can also act to activate the reader code if it isn’t already active.

Now that we’ve discussed how to write 0x10, 0x20, 0x30 - we can have another look at how we would write “Hello, world!” from first principles. We’ll be writing an extension method; we could start by extending IPipeWriter or WritableBuffer, but this would then only usable by pipelines-related code. There is an abstraction that we can use instead: IOutput. This works very similarly to WritableBuffer, and indeed WritableBuffer implements IOutput. But recall that WritableBuffer is a value-type (struct); this means that we also shouldn’t extend IOutput, as that would require boxing - we should instead extend T where T : IOutput:

public static unsafe void WriteUtf8<T>(

this T output, string value)

where T : IOutput

{ ... }

Now, this is when we start slamming into one downside of Span<T>: historically, it didn’t exist, so large parts of the .NET framework don’t know how to use it. This is changing, and it is likely that when pipelines is available, most key areas of the .NET framework have rich Span<T> support, but today, it can be problematic.

To write a string as a byte-sequence, we need to use an encoding. Historically, this has been provided by the Encoding type. Let’s assume that no Span<T>-specific version of encoding exists, and that all we have is Encoding. This can either work with arrays (byte[] and string/char[]) or pointers (byte* / char*). We cannot guarantee that we will have access to a byte[], because in the general case, Span<T> is not limited to T[], and we should avoid building in that dependency (even though we’d probably get away with it, because MemoryPool uses byte[] as an implementation detail).

So our escape hatch when we don’t have a Span<T> API is often to drop to pointers. All spans can be represented as a managed pointer (ref T), and a managed pointer - once pinned - can be treated as an unmanaged pointer (T*). This requires unsafe code, obviously.

Let’s assume that we expect our string to fit in a single block (not a great assumption really, but it works for our example):

public static unsafe void WriteUtf8<T>(

this T output, string value)

where T : IOutput

{

// good enough for ASCII demo...

output.Enlarge(value.Length);

var span = output.GetSpan();

int bytesWritten;

fixed (byte* bytes = &MemoryMarshal.GetReference(span))

fixed (char* chars = value)

{

bytesWritten = Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(

chars, value.Length,

bytes, span.Length);

}

output.Advance(bytesWritten);

}

Note that our utility method shouldn’t make any assumptions about the intent of the caller - they may wish to write more data into the block, so it shouldn’t Commit() the data. So our calling code becomes:

IPipeWriter writer = pipe.Writer;

var buffer = writer.Alloc();

buffer.WriteUtf8("Hello, world!\r\n");

await buffer.FlushAsync(); // flush calls commit

That was quite the marathon to just write a string, but it highlights a lot of the key API concepts, and shows how to minimize copies. We should expect that most of this basic functionality is readily encapsulated by library methods, so in reality we will only need this type of usage for more exotic scenarios. We should additionally keep in mind that the above implementation is simplistic: in real code, we might want to consider:

- utf-8 involves multi-byte characters, so we shouldn’t assume that

value.Lengthbytes are sufficient - for very large strings, even if they only contain characters in the ASCII range, we might need to use multiple blocks and encode in chunks; this means calling

Enlarge()andAdvance()once per loop iteration - we can optimize by asking: is there enough space assuming every character takes the maxiumum possible width to fit in a single block - if so: use a fast path

- for short strings, even if the worst case doesn’t fit, it might make sense to calculate the actual length to see whether it will actually fit in the available space, and if so: use a fast path

- in the multi-block case we need to think about whether the last character at the end of one block might span two blocks; do we only write entire characters, or do we track the intermediate state?

Which are all good reasons why we shouldn’t normally expect to have to write our own string encode methods; it turns out that strings are actually really awkward!

The one thing we still might want to do is to tell the pipe that we’ve finished sending - essentially closing the pipe in such a way that the reader knows that no more data should be expected; fortunately, this is simple:

writer.Complete();

It has been a long journey, but we’ve looked the fundamentals of creating a pipe and writing to it with the IPipeWriter API. We’ve introduced Memory<T> and Span<T>, and seen how to work with them. We’ve looked at how to drop to unsafe code against a Span<T> if we need to. And we’ve put some data into a pipe for a receiver to consume. In the next part, we’ll look at consuming data from a pipe.